The Bklyn Combine Honors

This February The Bklyn Combine decided to begin a tradition of honoring our ancestors for the tremendous legacy that they have left behind. Many of our heroes spent large portions of their lives dedicating their time, energy, and expertise to helping others and providing a blueprint for generations to come. The Combine Honors is a dedication that started during Black History Month but it will continue throughout the year and will highlight present and past individuals who impact us positively and have made a difference in our local and global communities. To learn more about any given honoree please feel free to reach out in our contact section or post a note on Instagram where you can also find these extraordinary individuals posted.

Fannie Lou Hamer

In 1964, Fannie Lou Hamer helped organize Freedom Summer, an African American voter registration movement, in her home state of Mississippi. She joined the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party in 1965 and worked with other activists to oppose the state’s all-white delegation. When she saw the power of white landowners battling Black people by denying them food, voting rights, land, and financial opportunities, she created a solution: the Freedom Farm Cooperative - a community-based, rural and economic development project.

Aside from suffering physical disabilities due to childhood polio, being the victim of police brutality, assaults, extortion, death threats, and suffering the horrors of a forced hysterectomy, Hamer risked her own wellbeing to improve the conditions of Blacks in America.

"If I fall, I'll fall five feet four inches forward in the fight for freedom."

– Fannie Lou Hamer

William L. Patterson

African American Communist and lawyer William L. Patterson was instrumental in laying the groundwork and strategy to fight Jim Crow and the hypocrisy of the American Rule of Law.

Patterson gave up a well-to-do life and thriving successful New York legal practice to challenge America his entire life, at times working with the great Paul Robeson who became a lifelong comrade in the struggle for freedom.

Patterson took on many civil rights injustices and was a legal architect and strategist in fighting the Scottsboro case in 1931, where African American boys were falsely accused of raping a white woman.

Patterson often traveled overseas to advance African American equality by fostering and leveraging international support. He was responsible for the “We Charge Genocide” petition to the Unite Nations. Patterson also challenged the American prison system before mass incarceration and the prison industrial complex became popular and defended members of the Black Panther Party (BPP).

Patterson possessed the foresight and critical analysis to effectively carry the freedom struggle of Black people into the global arena. He transformed into a revolutionary, fighting colonialism, racism, Jim Crow, Apartheid, and red-baiting his entire life. In Gerald Horne’s book, “Black Revolutionary: William Patterson and the Globalization of the African American Freedom Struggle,” which followed the famous murder case of Italian anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti (who had been falsely accused of murder), Patterson is quoted as saying “It was at this moment that a weighty realization dawned: ‘I came to the conclusion then that through the channels of the law and of more legal action [alone] the Negro would never win equality’ for ‘if a white worker like Tom Mooney and white foreigners like Sacco and Vanzetti could be so victimized, what chance was there for Negroes at the very bottom.'”

William Patterson laid the groundwork for future Black freedom fighters not sold on the idea that America’s colonial version of democracy and racialized capitalism was the citadel of civilization and justice.

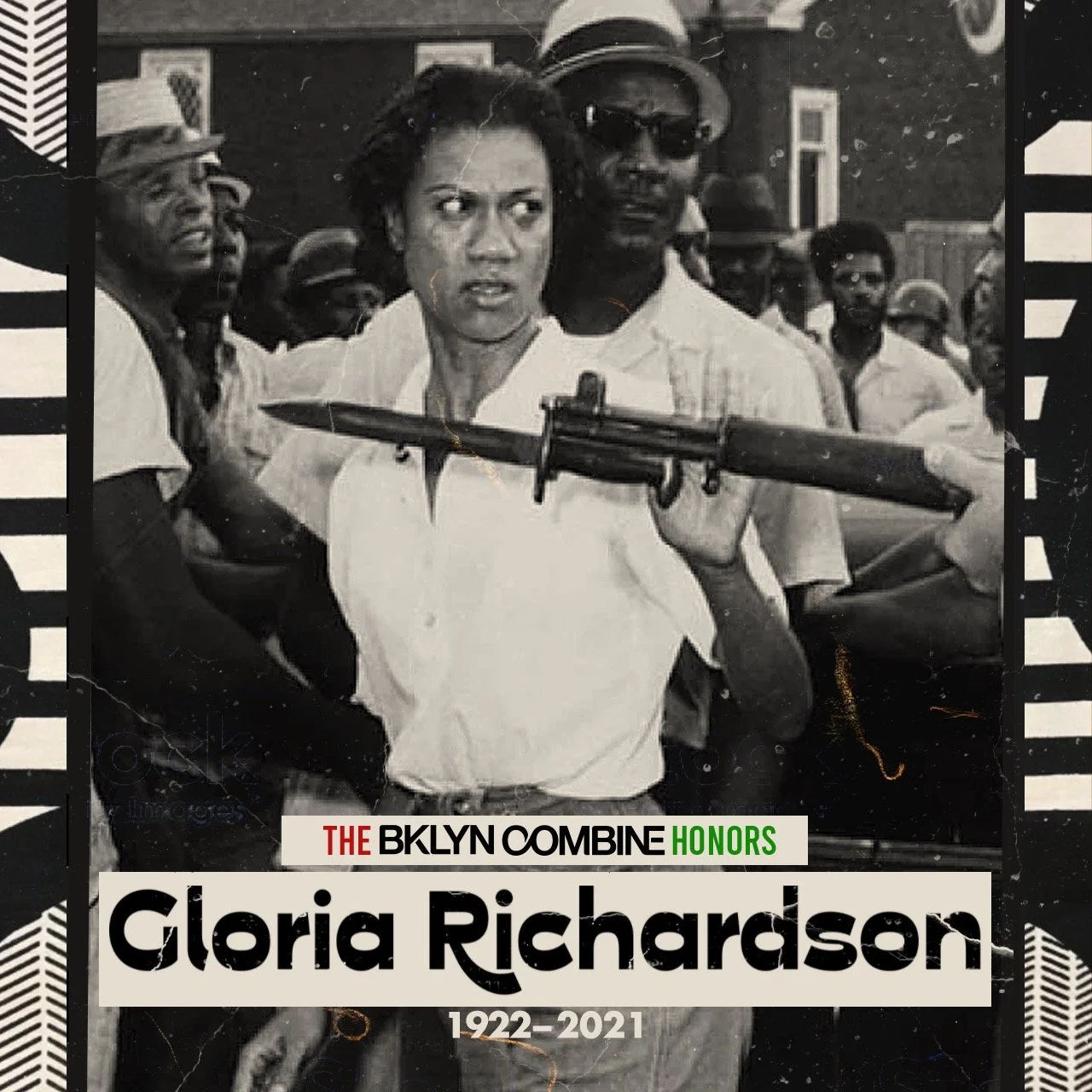

Gloria Richardson

Gloria Richardson was known as the "The lady general of civil rights," and someone Malcolm X identified as the paradigm for the Grass Roots in the Black Revolution. Richardson was born in Baltimore, Maryland, to parents who owned grocery stores in Cambridge's Second Ward, and her family was known locally for resisting the oppression of Black people. Activism was a regular feature of her daily childhood, and her own social work began in 1938 at Howard University, where she protested both at the local Woolworths and also the conditions at Howard. After graduating Howard, Richardson returned to Cambridge and led the 1960s Cambridge Movement and Cambridge Nonviolent Action Committee (CNAC).

The Cambridge Movement directed its work towards improving living conditions for the people of the Second Ward. Meanwhile, continuing militant CNAC protests angered both the Kennedy administration in nearby Washington, D.C. and national civil rights leaders. When the state of Maryland and federal negotiators, led by Robert Kennedy, proposed voting for the right of access to public accommodations in 1963, Richardson stated, "A first-class citizen does not beg for freedom. A first-class citizen does not plead to the white power structure to give [them] something that the whites have no power to give or take away. Human rights are human rights, not white rights."

Later in life, after marriage, moving to the northeast and nearing retirement, Richardson continued her cause-related work and joined the New York City Department for the Aging. She helped ensure businesses complied with laws that affected seniors, worked with Harlem Youth Opportunities Unlimited and was an advisor for the Black Action Federation (BAF).

Richardson left a legacy for everyone, especially Black women, to be unabashedly radical in the fight for social change and human dignity.

Richardson reminds us to fully commit to social change, otherwise we'll "keep protesting the same things another 100 years from now." – Gloria Richardson

Lucy Craft Laney

Lucy Craft Laney was an educator and civil rights activist. She was a visionary known for founding the first school for Black children in Augusta, GA in 1883. Her aptitude and dedication to learning at an early age solidified her as the perfect candidate to open a school.

Born free in 1854, in Macon, GA (11 years prior to the abolishment of slavery), Laney learned to read and write by age four. At age twelve, she was able to translate difficult passages in Latin. She later attended Atlanta University, graduating from the teacher’s training program. After ten years working as a teacher in several cities throughout Georgia, she opened her own school in the basement of Christ Presbyterian Church in Augusta. The state licensed it as Haines Normal and Industrial Institute. Laney presided as founder and principal for fifty years (1883-1933).

In 1918, Lucy Laney helped found the Augusta branch of the NAACP. She was also active in the Interracial Commission, the National Association of Colored Women, and the Niagara Movement.

Her friends and students included Mary McLeod Bethune, Nannie Helen Burroughs, W. E. B. Du Bois, Langston Hughes, and Madame C.J. Walker, just to name a few.

“God didn’t use any different dirt to make me than the first lady of the land.” – Lucy Craft Laney

George Taliaferro

George Taliaferro was the first Black player to be drafted in the NFL. He himself thought being drafted by the racist NFL was so unlikely that he signed with an African American league team. At the time of the draft the, then Washington Redskin owner George Preston Marshall, yelled toward Taliaferro “Niggers should never be allowed to do anything but push wheelbarrows”, according to the book Race and Football in America: The Life and Legacy of George Taliaferro.

Through it all, Taliaferro made 3 All-Pro teams in his 7-year career where he did it all on the field and set the table for thousands of African-American players after him to play in a league that is now majority Black.

Later in life, Taliaferro founded a branch of the Big Brothers Big Sisters Foundation, formed to help children in underprivileged communities. He returned to Indiana University (his alma mater) to become an affirmative action coordinator while serving as a special assistant to the president of the school. He later became dean of students at Morgan State University. George also contributed to several community endeavors like advising prisoners upon their release from prison.

Reflecting on a life filled with adversity as a result of racism, Taliaferro said, “I have been and I remain a thorn in the side of those who would think they are better than I am.” – George Taliaferro

Shirley Chisholm

Shirley Anita St. Hill Chisholm was born in Brooklyn, NY in 1924. Chisholm began a career of service in the areas of education and social services in New York City, serving as director of the Hamilton-Madison Child Care Center and then as an educational consultant for the City’s Bureau of Child Welfare. She became known as an authority on issues involving early education and child welfare and quickly evolved into a champion of racial and gender equality, joining the local chapters of the League of Women Voters, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the Urban League, and the Democratic Party club in Bedford Stuyvesant, Brooklyn.

In 1964, Chisholm successfully ran for a seat in the New York State Legislature and in 1968, became the first Black woman to earn election to Congress where she worked on the Education and Labor Committee and was a founding member of the Black Caucus. There, “Fighting Shirley” introduced more than 50 pieces of legislation and championed racial and gender equality, the plight of the marginalized, and ending the Vietnam War.

Chisholm became the first Black candidate to make a bid for the presidency of the United States from a major party when she ran for the Democratic nomination in 1972. Discrimination followed Chisholm’s quest for the nomination as she was blocked from participating in televised primary debates. After taking legal action, she was permitted to make just one speech, yet still garnered 152 of the delegates’ votes (10% of the total) despite an under-financed and heavily contended campaign. After leaving Congress in 1983, Chisholm taught at Mount Holyoke College and lectured nationally.

Shirley Chisholm is a true pioneer and champion of the fighting spirit; she let no perceived barrier, whether race or gender, prevent her from performing her life’s work.

“You don't make progress by standing on the sidelines, whimpering and complaining. You make progress by implementing ideas.” – Shirley Chisholm

Nannie Helen Burroughs

Nannie Helen Burroughs was an educator, orator, suffragist, and civil rights activist born on May 2, 1879, in Orange, VA. By 1883, Burroughs and her family relocated to Washington D.C. to seek better opportunities and she graduated with honors from M Street High School (now Paul Laurence Dunbar High School). It was here she organized the Harriet Beecher Stowe Literary Society and met her role models Anna J. Cooper and Mary Church Terrell, who were active in the civil rights suffrage movements.

Despite her academic performance, Burroughs was refused a Washington D.C. public school teaching position (likely because she had dark skin) and she decided to open her own school to educate and train Black women. Relying on small donations from the community, Burroughs opened the National Training School for Women and Girls in 1908. The school provided evening classes (taught by Burroughs herself) for women who had no other means for education; racial pride, respectability, and work ethic were its driving ideologies. These qualities were seen as extremely important to bring Black women into the larger public sphere. Many disagreed with Burroughs’ teaching women skills that did not directly apply to domestic housework but she continued her work unflinchingly. Burroughs sought to challenge and change the very narrative of the Black community, training Black women from a young age to become efficient wage workers and community activists while reinforcing the ideals of self-respect and self-empowerment.

Burroughs was also a published playwright. In the 1920s she wrote “The Slabtown District Convention” and “Where Is My Wandering Boy Tonight?”, one-act plays which were popular during their time.

Burroughs fought tirelessly so that Black women would have the right to an education, fair wages, and leadership in this country.

“When the Negro learns what manner of man he is spiritually, he will wake up all over. He will stop playing white even on the stage. He will rise in the majesty of his own soul.”

- Nannie Helen Burroughs

Arturo Schomburg

Writer, activist, and historian Arturo Alfonso Schomburg was born in Santurce, Puerto Rico to a freeborn Black midwife from St. Croix and a German immigrant to Puerto Rico. While in grade school, one of his teachers claimed that Black people had no history, heroes, or accomplishments. Inspired by this, Schomburg determined that he would curate, document, and celebrate the accomplishments of Africans on their own continent and in the broader diaspora.

Schomburg immigrated to Harlem in 1891; his passion for preserving Black culture was informed by his allegiance to Puerto Rican and Cuban independence groups and settled into a Puerto Rican enclave of a Cuban area known for its nationalist intellectuals. He became a member of the "Revolutionary Committee of Puerto Rico" and co-founded “Las Dos Antillas,” an organization that provided weapons, money, and medical supplies to aid the independence struggles of Cuba and Puerto Rico.

Schomburg continued to build and develop scholarly organizations like the “Negro Society for Historical Research” and the “American Negro Academy,” aimed at bringing together scholars, editors, and activists to refute racist scholarship, promote Black and Brown claims to individual, social, and political equality, and provide a more historically accurate depiction of our history and contributions to this world.

Schomburg would publish many works, none more notable than his essay The Negro Digs Up His Past, devoted to the intellectual life of Harlem. Our renowned historian John Henrik Clarke told of being so inspired by the essay that he left his home in Columbus, GA, to seek out Schomburg to expand his studies in African history.

The New York Public Library purchased Schomburg's private collection in 1926 and he was appointed curator of what is today known as the Arthur Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

“We need the historian and philosopher to give us with trenchant pen, the story of our forefathers, and let our soul and body, with phosphorescent light, brighten the chasm that separates us. We should cling to them just as blood is thicker than water.”

– Arturo Alfonso Schomburg

Rosetta Tharpe

Sister Rosetta Tharpe is considered the “The Godmother of Rock-and-Roll” and one of the first gospel musicians to gain mass appeal amongst both Rhythm and Blues and Rock-and-Roll audiences. At age six, Tharpe joined her mother as a regular performer in a traveling evangelical troupe as a singer and brilliant guitarist. She ascended to stardom in the 1930s and 1940s with her recordings, characterized by a unique mixture of spiritual lyrics and electric guitar that was groundbreaking and critical to the birth of Rock-and-Roll music.

Tharpe heavily influenced early Rock-and-Roll musicians such as Little Richard, Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins, Chuck Berry, Elvis Presley and Jerry Lee Lewis. Her 1945 hit "Strange Things Happening Every Day" was the first gospel record to cross over, hitting no. 2 on the Billboard "race records" chart (what would later become the R&B chart). The recording has been cited as a precursor to Rock-and-Roll, and alternatively cited as the first Rock-and-Roll record.

Tharpe was a trailblazer in her techniques and she was among the first popular recording artists to use heavy distortion on her electric guitar, paving the way for the rise of electric blues. Her way of play had a profound influence on the development of British blues in the 1960s. Willing to cross the line between religious and secular by performing her style of music in nightclubs and concert halls, Tharpe pushed spiritual music into the mainstream.

Tharpe, a queer woman, unapologetically performed her music with an openness for love and sexuality. During a time where guitar talent and ability were considered for men only, Tharpe proved that talent has no gender, demonstrating her talent through hbattles at world renowned venues like the Apollo and the Cotton Club. All-time musicians, including Aretha Franklin, Jerry Lee Lewis and Isaac Hayes, have identified her singing, guitar playing and showmanship as an important influence on their music and careers.

“Can’t no man play like me.” – Sister Rosetta Tharpe

Fred Hampton Sr.

Fredrick Allen Hampton Sr., Deputy Chairman of the Black Panther Party For Self-Defense (BPP), began a life of service in suburban Chicago in the late 1940s. As a child he hosted neighborhood breakfast programs to help feed his community, and joined the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) soon into his young adulthood. A natural leader and brilliant orator, he organized local youth dedicated to improving the impoverished socioeconomic conditions in his community while at the NAACP. Soon thereafter, Chairman Fred joined the BPP where he emphasized health, nutrition, self-defense from police and government brutality, and anti-racist, multicultural alliances amongst the local gangs and other like-minded community organizations (the Rainbow Coalition was one of the many fruits of this labor). Chairman Fred, at just 21 years old, contributed a lifetime‘s worth of sacrifice to the struggle of the marginalized and disenfranchised.

“We're going to fight racism not with racism, but we're going to fight with solidarity. We say we're not going to fight capitalism with Black capitalism, but we're going to fight it with socialism.”

- Deputy Chairman Fred Hampton

Hosea Easton

Reverend Hosea Easton was a lecturer, writer, abolitionist, and minister. The Easton’s were one of the most notable Black families in New England who could trace their lineage in America to 1690. Hosea learned courage and activism early as a child.

The Congregational church attended by the Easton family built a “negro porch” in the back and required all Black members of the congregation to sit there during services. Hosea’s parents refused. The family continued to sit on the main floor of the church until being physically removed. This same struggle took place in a number of churches the Eastons attempted to join. As a child, Rev. Hosea Easton engaged in at least five acts of civil disobedience before he was a teenager. He and his family were the first African Americans known to have engaged in sit-ins for racial justice.

In the 1820s, Hosea became a minister and effective abolitionist agitator. Rev. Hosea first came to public attention in 1828 with a Thanksgiving Day address in Providence, RI, attacking racism and slavery. It was a frank, explicit, angry condemnation of the brutalities of slavery, mixed with the call for spiritual uplift of Black people. In this sermon, he also criticized the African Colonization Society, a movement led by whites to remove all American Blacks from the country. This was a “diabolical pursuit,” Rev. Hosea preached, “where they will steal the sons of Africa… bring them to America, keep them in bondage for centuries… then transport them back to Africa by which means America gets all her drudgery done at little expense.” Rev. Hosea Easton died on July 6, 1837, at 38 years of age. Several months before his death, he published his Treatise on The Intellectual Character, and the Civil and Political Condition of The Colored People of The United States: Treatise in which he concluded that racial uplift could not succeed in a white-dominated society that physically terrorized Black Americans. Easton, along with fellow abolitionist David Walker, co-founded the Massachusetts General Colored Association, and also debunked scientific racism that flowed through American academia and social sciences.

Frances Cress Welsing

Dr. Frances Cress Welsing was born the child of a physician and a teacher in Chicago, Illinois in 1935. A career psychiatrist, scholar, author and activist, Dr. Cress Welsing earned her M.D. at Howard University where she began to develop her theories on society, race and racism. She spent nearly twenty-five years working as a staff physician for Washington D.C.’s Department of Human Services, addressing issues such as drug use, murder, teen pregnancy, infant mortality, incarceration, and unemployment in Black and Brown communities.

Dr. Cress Welsing critically analyzed and theorized the root causes of racism and white supremacy as survival mechanisms applied by non-melanated people as a means of global survival. She self-published her first work, The Cress Theory of Color-Confrontation, in 1970, as a foundational element and precursor to her most well-known book The Isis Papers: The Keys to the Colors (1992), which outline her philosophies.

Dr. Cress Welsing developed her own definition of racism, and referred to racism and white supremacy synonymously; she considered crises such as AIDS and drug addictions as chemical and biological warfare.

Aside from her published theories, Dr. Cress Welsing was a proponent of a strong Black family unit. She advised Black men and women to delay having children until their thirties and instead focus on thoroughly educating themselves so as to create a stronger community of thinkers to challenge white supremacy.

“Racism (white supremacy) is the local and global power system dynamic... whether consciously or subconsciously determined; this system consists of patterns of perception, logic, symbol formation, thought, speech, action and emotional response, as conducted simultaneously in all areas of people activity: economics, education, entertainment, labor, law, politics, religion, sex, and war.” – Dr. Frances Cress Welsing

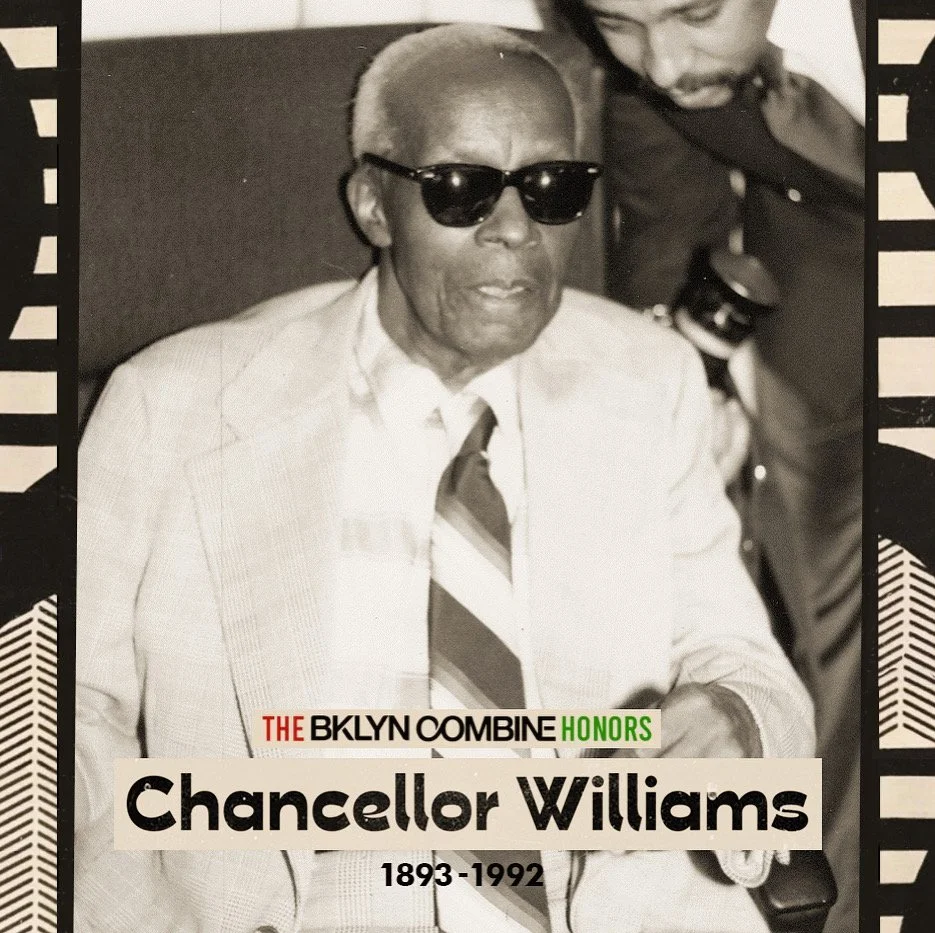

Chancellor Williams

Dr. Chancellor James Williams was born on December 22, 1893, in Bennettsville, SC. His father was born into slavery and gained his freedom after the American Civil War. A noted sociologist, historian and writer, Dr. Williams directed his life’s work towards a scholarly, factual historical accounting of African civilizations and achievements and the many self-ruling civilizations that thrived on the continent long before the arrival of Europeans or Asians. His last study, completed in 1964, covered 26 countries and more than 100 language groupings and he remains a key figure to the Afrocentrist discipline: the study of world history that focuses on the history of people of recent African descent.

Dr. Williams is best known for his powerful and narrative shifting book “The Destruction of Black Civilization: Great Issues of a Race From 4500 B.C. to 2000 A.D.” (1971), in which he outlines the multiple global achievements and contributions of African people and the bias of white academics who would distort the historical retelling of our rich, great past. Dr. John Henrik Clarke, a contemporary of Dr. Williams’ and a giant amongst scholars in his own right, described the work as "a foundation and new approach to the history of our race" where Dr. Williams successfully "shifted the main focus from the history of Arabs and Europeans in Africa to the Africans themselves -- a history of the Blacks that is a history of Blacks."

“The term 'black' was given a rebirth by the black youth revolt. As reborn, it does not refer to the particular color of any particular person, but to the attitude of pride and devotion to the race whose homeland from times immemorial was called 'The Land of the Blacks.' Almost overnight our youngsters made 'black' coequal with 'white' in respectability, and challenged the anti-black Negroes to decide on which side they stood.“ - Dr. Chancellor Williams

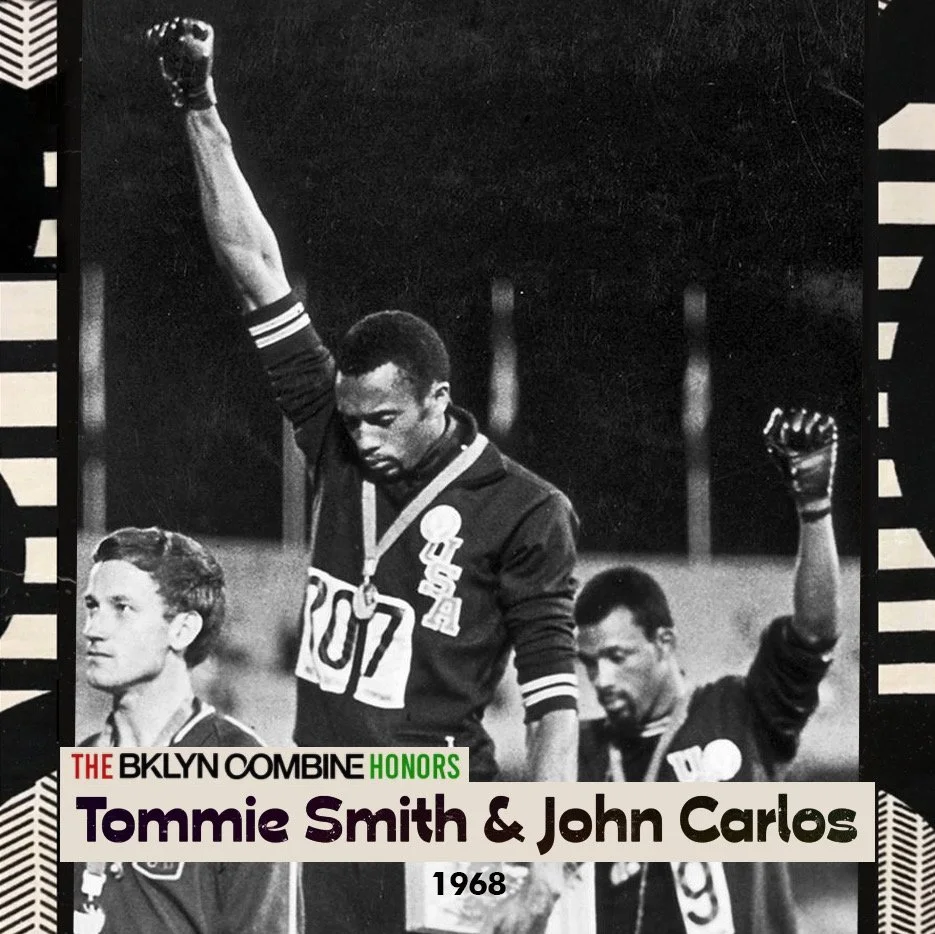

Tommie Smith & John Carlos

Tommie Smith and John Carlos are track and field athletes who used the 1968 Summer Olympics stage as a platform to bring the world’s attention to the struggle for human rights. Smith and Carlos won the gold and bronze medals respectively in the 200 meters, and, during the medal ceremony, each raised a black-gloved fist in solidarity for the duration of the United States national anthem. The two also chose to receive their medals shoeless while wearing black socks to represent Black poverty. Smith wore a black scarf around his neck to represent Black pride, and Carlos wore a beaded necklace he described as "for those individuals that were lynched or killed and that no-one said a prayer for, that were hung and tarred. It was for those thrown off the side of the boats in the Middle Passage."

Smith and Carlos were banned from the Games and their brave demonstration of strength cost each personally and professionally in the subsequent years. When they returned home they were ostracized by large parts of the sporting community and received death threats for their actions.

In his autobiography, “Silent Gesture,” Smith described the gesture as not a Black Power salute per se, but rather a "human rights" salute. The demonstration is regarded as one of the most impactful political statements in the history of the Olympics.

“I don't think it's necessary to go to any game to make a stand just because you are there. The stand is made from the heart, and you can do that in the grocery store.” – Tommie Smith

“The bottom line is, if you stay home, your message stays home with you. If you stand for justice and equality, you have an obligation to find the biggest possible megaphone to let your feelings be known. Don't let your message be buried and don't bury yourself.” – John Carlos

Ivan Van Sertima

A British-Caribbean scholar, Ivan Gladstone Van Sertima was a literary critic, linguist, educator, and anthropologist, that worked to transform how African history was taught. In 1976, Van Sertima authored his most famous book, “They Came Before Columbus” where he argued that people of African origin came to America long before Christopher Columbus arrived in 1492.

Van Sertima was born in Guyana, where he spent his early years completing primary and secondary schools. He eventually moved to England where he received his B.A., with honors, in 1969 from the London School of Oriental and African Studies. A multi-talented scholar, he learned to speak Swahili and Hungarian fluently. Among his different endeavors, Van Sertima did broadcasts about literature for the BBC, wrote poetry, compiled a dictionary of legal terms in Swahili, and wrote a series of essays on Caribbean literature.

Following graduation from college, Van Sertima moved to the U.S. earning his Master’s degree and becoming an Associate Professor of African Studies at Rutgers University. He founded the Journal of African Civilizations, which helped transform how African history was viewed and taught. Its articles described early African advances in agriculture, mathematics, arts, engineering, architecture, writing, medicine, astronomy, and navigation.

In 1974 Van Sertima was asked to join UNESCO’s International Commission for Rewriting the Scientific and Cultural History of Mankind. And, from 1976 to 1980 he was asked by the Nobel Committee of the Swedish Academy to nominate candidates for the Nobel Prize in Literature.

"The African presence in America before Columbus is of importance not only to African and American history but to the history of world civilizations. It provides further evidence that all great civilizations and races are heavily indebted to one another and that no race has a monopoly on enterprise and inventive genius.”

– Ivan Van Sertima

Bayard Rustin

Bayard Rustin, born on March 17, 1912, in West Chester, PA, was a champion in social movements for civil rights. His family’s early involvement in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) helped shape his fight for human rights and, in his youth, Rustin campaigned openly against racially discriminatory Jim Crow laws.

After finishing high school, Rustin attended Wilberforce University in Ohio, and Cheyney State Teachers College, both historically Black schools, before landing at the City College of New York. He quickly developed into a tremendous figure in the civil rights movement and a close adviser to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.; he was the principal organizer of King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference to strengthen King's leadership through nonviolence, and he also organized the Freedom Rides, where civil rights activists who rode interstate buses into the segregated South challenged the laws that segregated public buses.

Rustin coordinated with A. Philip Randolph on the March on Washington Movement to press for an end to racial discrimination in employment and pressure the U.S. government into providing fair working opportunities for Black Americans as well as desegregating the armed forces via threat of mass marches on Washington, D.C. He is perhaps best known as the organizer for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom (or simply the “March on Washington”) to advocate for the civil and economic rights of the disenfranchised and the site of Dr. King’s historic "I Have a Dream" speech. Rustin also directed a one-day student boycott of New York City’s public schools in protest against racial imbalances in that system (more than 400,000 New Yorkers participated in the one-day boycott) and subsequently served as the head of the AFL–CIO's A. Philip Randolph Institute, which promoted the integration of formerly all-white unions and promoted the unionization of Black Americans. Rustin, a gay man, was also a staunch proponent of gay rights and heavily involved in the gay rights movement.

“To be afraid is to behave as if the truth were not true.” - Bayard Rustin

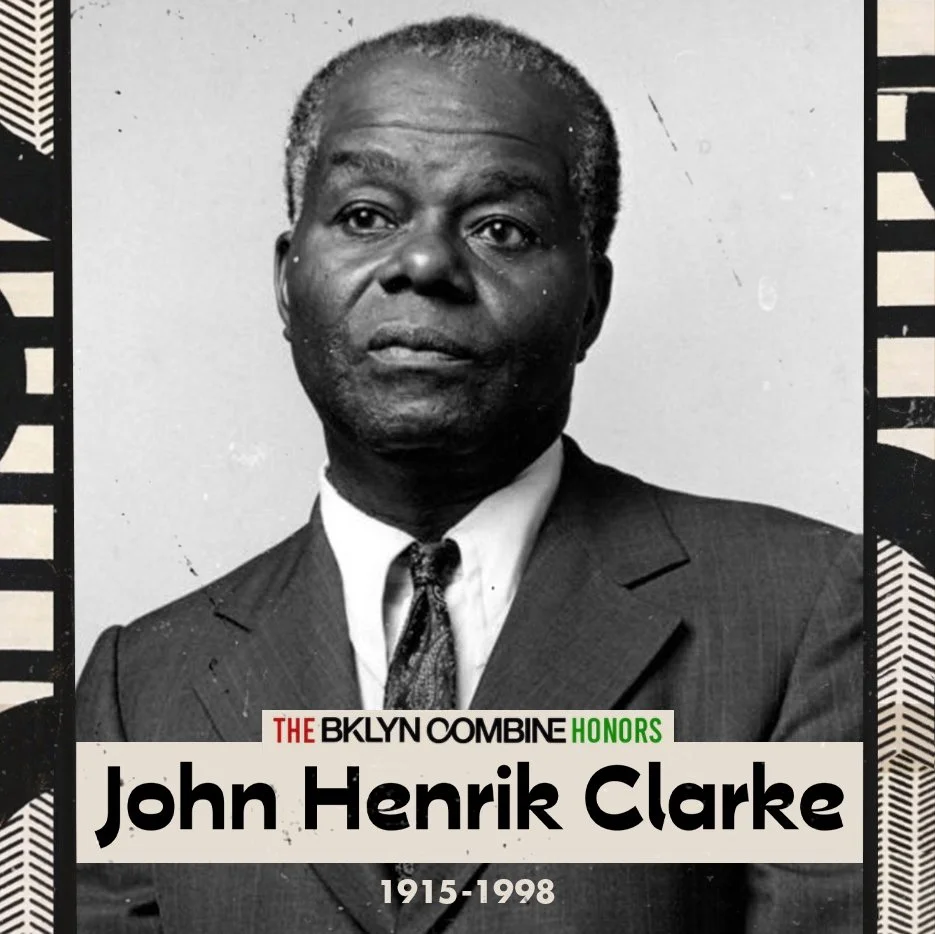

John Henrik Clarke

An endearing figure in the Bklyn Combine, John Henrik Clarke was a professor, historian, and black nationalist. A pioneer in the development of Pan-African and Africana studies in the U.S., Dr. Clarke was a dominant voice in teaching an Afrocentric view of history. His extensive career as a professor and scholar preceded him and laid the groundwork for generations to come. To many, Dr. Clarke is considered the grandfather of African History.

Dr. Clarke migrated to Harlem from Columbus, GA in 1933 at the age of 18. Clarke developed as a writer and lecturer during the Great Depression. His development as a scholar came through his active involvement in several study circles such as the Harlem History Club and the Harlem Writers’ Workshop. He joined the U.S. Armed Air Forces during World War II, serving from 1941 to 1945 as a non-commissioned officer, ultimately attaining the rank of master sergeant.

While in Harlem, Dr. Clarke studied intermittently at NYU, Columbia University, Hunter College, the New School of Social Research, and the League for Professional Writers. Dr. Clarke undertook the study of Africa, studying its history, while under the mentorship of scholars like Arturo Alfonso Schomburg. Over the duration of his career, Dr. Clarke became one of the foremost historians of African and African American history. He was the founding chairman of the dept. of Black and Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College, for almost 20 years. Additionally, Clarke was a visiting Professor of African History at Cornell University.

His natural storytelling capabilities made his lectures a thing of folklore. A natural orator and the everyday man’s scholar, it was truly a gift to observe Dr. Clarke’s uncanny ability to command an audience. He wrote several books and co-founded with Leonard Jeffries, the African Heritage Studies Association, which supported scholars in areas of history, culture, literature, and the arts.

“A people must have a name that relates them to land, history, and culture… a name of a people has to relate to a land of origin.”

– John Henrik Clarke

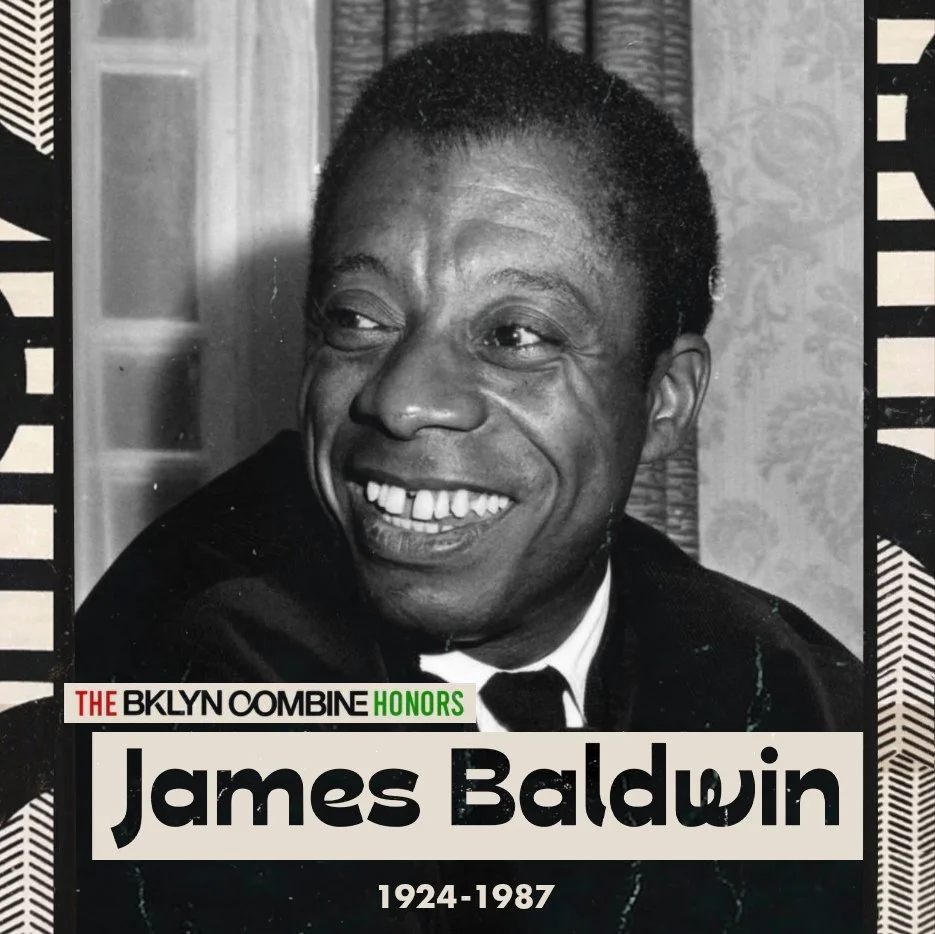

James Bald

A prolific writer and activist, James Baldwin was a master of reflecting on the Black experience in America. Through numerous essays, poems, novels, plays, and speeches, his eloquent voice touched on the pain and struggle of Black Americans. Baldwin was able to mirror the aspirations and disappointments of Black people in a hostile society while criticizing racial inequity. In tandem with the civil rights movement of the 1950s, Baldwin published his first novel, “Go Tell It On The Mountain”, in 1953, followed by his first collection of essays, “Notes of a Native Son”.

In his work, Baldwin explored themes of racial tension, masculinity, sexuality, and class, crafting deeply intricate narratives. He also dealt with taboo themes like homosexuality and interracial relationships. By describing life as a Black man in a white American, Baldwin created socially relevant, psychologically penetrating literature; and readers responded.

Baldwin used his oratory gifts throughout his career as an outspoken civil rights activist. He worked for a number of years as a freelance writer in NY. He later secured a writing grant in 1948, then headed to Paris, where he created enough distance from the racially divided America he knew so well; to critically write about it from a clearer vantage point.

Over the next ten years, Baldwin moved from Paris to New York to Istanbul, writing two books of essays as well as two novels that explored class and racial tensions with eloquence. He remained an important figure in the civil rights struggle throughout the 1960s. After the assassinations of his friends Medgar Evers, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X, Baldwin returned to St. Paul de Vence, France, where he worked on a book about the disillusionment of the times, entitled, “If Beale Street Could Talk”. This book was later adapted into the Academy Award-winning film of the same name in 2018.

“It is very nearly impossible to become an educated person in a country so distrustful of the independent mind.” – James Baldwin

Gwendolyn Brooks

Poet Laureate Gwendolyn Brooks was a regular contributing writer to The Chicago Defender by the time she graduated high school in the 1930s. As a teenager, she began chronicling the black experience with such poetic prose that she drew the attention and encouragement for her literary work from James Weldon Johnson, Richard Wright, and Langston Hughes.

She was a master of language, creating a style that blended traditional ballads, sonnets, and blues rhythms that asserted black people's humanity in America. In 1950, Brooks was the first Black person to win the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. A prominent poet, author, and teacher, Brooks had an extraordinary literary career created work that celebrated ordinary people in her community, highlighting the everyday struggles of Black life.

She was named poet laureate for Illinois in 1968, the first black woman appointed as a consultant in poetry to the Library of Congress in 1985, and the first Black woman inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

On any given day, regardless of where you find yourself in the struggle, Brooks reminds us that "Even if you are not ready for day, it cannot always be night" -Gwendolyn Brooks

Arthur Ashe

Arthur Robert Ashe Jr. (July 10, 1943 – February 6, 1993) is well-known for his multiple tennis accomplishments, but his lifelong work as an activist and humanitarian, attacking segregation and Apartheid in furtherance of the advancement of civil and human rights, is where his legacy is most impactful.

Ashe began playing tennis in the segregated courts of Richmond, Va., and quickly rose in the amatuer and professional rankings. In 1969, already a decorated college and world-class professional tennis player, Ashe applied for a visa to South Africa to compete in the South African Open, but was unable to play (despite his No. 1 United States tennis ranking) due to the systemic segregation and racism of Apartheid. Ashe used his celebrity and his voice to advocate for human rights against the South African Apartheid regime, writing for Time Magazine and the Washington Post and continued his activism through his writings and public speakings. In 1983 he cofounded Artists and Athletes Against Apartheid, which brought awareness of Apartheid policies and lobbying for sanctions and embargoes against the South African government. His tireless activism was critical to repealing apartheid legislation in Africa.

Arthur Ashe is believed to have contracted human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) after a tainted blood transfusion related to heart surgery. He bravely went public with his condition, raising money for research into treating, curing and preventing the HIV and AIDS diseases claiming countless lives in institutionalized Black and Brown communities (especially African) at a genocidal rate. He implored the world community to address HIV/AIDS as a world issue, while also founding the Arthur Ashe Institute for Urban Health to address the inadequate healthcare provided to the underserved and under-resourced Black and Brown populations worldwide.

“True heroism is remarkably sober, very undramatic. It is not the urge to surpass all others at whatever cost, but the urge to serve others at whatever cost.”

– Arthur Ashe

Dr. Amos Wilson

Dr. Amos Wilson was born in 1941 in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. He was a brilliant author, psychologist, social theorist, social worker, PanAfricanist, lecturer, and wealth of knowledge. He helped contextualize the condition of Black people in the U.S. as a result of racism and white supremacy. Dr. Wilson's work relied upon criminal attorneys, Mental health experts, social workers, and other professionals. Through his intellect and scholarship, Dr. Wilson became one of the most eloquent speakers on Black power and Black nationalism, and the condition of Black people. In many regards, Dr. Wilson perfectly described the relationship between racism-white supremacy and the deprivation in the Black community. Dr. Wilson also provided solutions to be studied and expanded upon for the liberation and survival of Black people in America.

His vast collection of scholarly work is essential in understanding the current state of Black America. In "The Falsification of Afrikan Consciousness," Wilson reminds us that "if we don't know ourselves, not only are we a puzzle to ourselves; other people are also a puzzle to us as well. We assume the wrong identity and identify ourselves with our enemies. If we don't know who we are then we are whomever somebody tells us we are".

– Dr. Amos Wilson

Claudette Colvin

A pioneer of the 1950s civil rights movement and retired nurse aide, Claudette Colvin was a maverick. At the age of 15, she refused to move to the back of the bus and give up her seat to a white person on a segregated bus — 9 months before Rosa Parks did the same courageous act.

Colvin was one of five plaintiffs in the first federal court case related to the 1955 Montgomery bus boycott. Filed the following year, as Browder v. Gayle, it challenged bus segregation in the city. She was wrongly convicted of assaulting a police officer and in a recent turn of events, on Nov. 24, 2021, Montgomery County Family Court issued an order granting to have her criminal record expunged.

Colvin’s story was a predecessor to the Montgomery bus boycott movement (which gained national attention), but she rarely told it after moving to New York City. Colvin worked as a nurse's aide in Manhattan for 35 years, retiring in 2004.

"All I remember is that I was not going to walk off the bus voluntarily."

– Claudette Colvin

Jamil Al-Amin

Jamil Al-Amin, formerly known as H Rap Brown, is one of the most outspoken Black liberators in American history. He once got into a heated discussion with Lyndon Johnson in the White House. His resistance to White Supremacy and racism resulted in having a Federal anti-riot act named after him (The Rap Brown Law). Amin was a son of the South who had followed his older sibling to fight racism in Washington D.C.

After protesting across the country in D.C., Alabama., and Mississippi, he supported a Maryland rally known later as the Cambridge movement led by Gloria Richardson. At the rally, he stated, "if America don't come around, we're going to burn America down.” That evening, 17 buildings were set on fire and destroyed. He became a target of the FBI’s COINTELPRO program, with an FBI memo calling for his neutralization. After the Cambridge incident, Brown was charged with carrying a gun across state lines and was defended by Murphy Bell and William Kunstler. His trial was to be held in Cambridge, MD, but after the Cambridge courthouse was bombed, he disappeared for 18 months and was listed on the FBI's Top 10 Most Wanted List.

In 1971, following an alleged attempted robbery and reported shootout with NYPD, he was arrested and served five years in Attica. After release, he moved to Atlanta, GA, and became Imam of "The Community Mosque of Atlanta" and a local grocery store owner. He provided mentorship, spiritual guidance, and leadership to Atlanta's West End community for over 20 years. Then in 2000, Sheriffs went to Al-Amin's home to attempt to execute an arrest warrant on a 1999 charge of speeding, auto theft, and impersonating a police officer. A series of events soon led to a shootout between the officers and an occupant of an approaching black Benz. The exchange left Deputy Kinchen dead and Al-Amin serving a life sentence in ADX.

In his struggle for Black Power, the freedom fighter, change agent, and dynamic orator was no stranger to violence. In our struggle, he noted, "violence is as American as cherry pie." Today he reminds us not to confuse a movement with a struggle.

"Movement is only a phase . . . The struggle is an ongoing process"

–Jamil Al-Amin

Bessie Coleman

Born in Atlanta, Texas in 1892, a courageous trailblazer was born. Her name was Bessie Coleman and she went on to become the first Black woman and the first Native American to hold a pilot’s license. At a time when at least nine Black men were lynched between 1890 and 1920 in nearby Paris, Texas. Coleman grew up in extreme poverty and racial segregation, but despite this fact, she accomplished becoming a Civil Aviator when very few American women of any race had pilot's licenses.

Coleman was denied admission to every flying school she had approached because she was both black and a woman, so she decided to learn to fly in France. With great determination, Coleman learned French at a Berlitz school in Chicago, withdrew her savings, got some additional financial help from her employer, and set off for Paris in 1920, only to return to the U.S. with an international pilot's license from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale.

Over the next few years, Coleman became a celebrated pilot and flew in countless national air shows. She became popularly known as “Brave Bessie” for her death-defying aerial stunts and being the revolution that she was, declined opportunities to perform at locations that wouldn't admit Blacks. In the following years, she used her notoriety to encourage other African Americans to become pilots.

"I decided blacks should not have to experience the difficulties I had faced, so I decided to open a flying school and teach other black women to fly." – Bessie Coleman

Kwame Ture

Kwame Ture (originally Stokely Charmichael), was a prominent civil rights activist, organizer, and Black nationalist. A global Pan-Africanist at heart, while still a freshman at Howard University, Ture joined the newly formed Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). He felt compelled to add-on to the struggle so he joined the Freedom Riders. He was very active in the Civil Rights Movement, taking a bus tour through the South to challenge segregation. As a result, he was arrested several times while protesting. This did not deter the young revolutionary. He popularized his philosophy of Black Power, later becoming Prime Minister of the Black Panther Party. Ture spent the subsequent years speaking around the country and writing essays on Black nationalism.

Ture immigrated to New York City from his place of birth, Trinidad. He completed high school then enrolled at Howard University in 1960. There he joined the SNCC and the Nonviolent Action Group. Ture continued his involvement with the civil rights movement and later became one of the more popular and controversial Black leaders in the forefront of the movement.

FBI director, J. Edgar Hoover, targeted Ture under the COINTELPRO program because if his growing popularity, so he moved to Africa in 1968. He re-established himself in Ghana, and then traveled to Guinea where he adopted the name Kwame Ture, and began campaigning internationally for revolutionary socialist Pan-Africanism.

“We been saying ‘freedom’ for six years. What we are going to start saying now is ‘Black Power.’” – Kwame Ture

Paul Robeson

Paul Robeson epitomized the 20th-century Renaissance man. His father, who was enslaved in North Carolina, ran away to fight for the North during the Civil War and eventually settled and raised Paul and his siblings in Princeton, NJ. That fighting spirit made its way into Paul, and he rose to remarkable heights as an All-American athlete, lawyer, activist, singer, stage & screen actor. Throughout the 1920s, he was the most celebrated and esteemed African American in the U.S. and likely the world. However, as his ideological development emerged and he began to critique white power and capitalism publicly, Robeson was labeled a psychopath and was soon despised by many.

In 1915, Robeson won a four-year academic scholarship to Rutgers University. Despite violence and racism from teammates, he won 15 varsity letters in sports (baseball, basketball, and track) and was twice named to the All-American Football Team. He received the Phi Beta Kappa key in his junior year, belonged to the Cap & Skull Honor Society (an organization that rewards excellence in academics, athletics and the arts, achievements at Rutgers), and graduated as Valedictorian.

Robeson then attended Columbia Law School (1919-1923), where he met and married Eslanda Cordoza Goode. He took a position with a law firm but left the practice of law to use his artistic talents in theater and music to promote African and African-American history and culture. He would use his deep baritone voice to promote Black spirituals, to share the cultures of other countries, and to benefit the labor and social movements of the time. In London, Robeson earned international acclaim for his lead role in Othello.

During the 1940s, Robeson would continued to perform and to speak out against racism, in support of labor, and for peace. A champion of working people and organized labor, he spoke and performed at strike rallies, conferences, and labor festivals worldwide. He also headed an organization that challenged President Truman to support an anti-lynching law.

"The history of the capitalist era is characterized by the degradation of my people."

– Paul Robeson

Assata Shakur

The Black Liberation Army (BLA) was a revolutionary organization that operated in the U.S. in the 1970s. Composed mostly of Black Panther Party (BPP) members, one of the BLA’s most infamous members was Assata Shakur f.k.a. JoAnne Chesimard. In May of 1973, Shakur was stopped on the NJ Turnpike “allegedly for a faulty rearlight”. In the car with Shakur were fellow BLA members, Zayd Malik Shakur and Sundiata Acoli. Moments after they were pulled over, both Zayd and a state trooper were dead, and Assata and another state trooper were shot and wounded in a shootout. In 1977, Shakur was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison, however, two years later she escaped and has been a fugitive ever since. As a result, the FBI placed the 74-year-old on its list of the top 10 most-wanted terrorists. To this day, there is a $2M reward for her apprehension.

Shakur moved from NY to NC in 1950 with her grandparents at age 3 following her parents’ divorce. It was a time of segregation and Jim Crow laws so she got an early lesson from her grandparents in personal dignity and Black pride creating her foundation in activism.

Shakur returned to NY and later became involved in political activism at BMCC and City College, NY. She was arrested for the first time (with 100 other students) in 1967 on charges of trespassing. The group had chained an entrance to a college building to protest the low number of Black faculty and lack of a Black studies program.

Immersed in the movement at that time, Shakur moved to Oakland, CA, where she joined the BPP as an organizer, overseeing protests and community education programs. Upon her return to NYC, she led the BPP chapter in Harlem, coordinating the Free Breakfast Program for children, free clinics, and community outreach.

Shakur has lived in Cuba since her escape, and was the first woman to be added to the FBI’s Most Wanted Terrorists list since 2013.

“No one is going to give you the education you need to overthrow them. Nobody is going to teach you your true history, teach you your true heroes, if they know that that knowledge will help set you free.” – Assata Shakur

Malcolm X

Malcolm X is the standard of Black intellect and consciousness. His understanding of the dynamics of European thought and behavior allowed him to speak and think with rare clarity regarding his understanding of the condition of Black people globally. Malcolm was on the right side of history; in many regards we have not done a good job of taking heed to his lessons, observations and uncanny ability to organize and wake those asleep. Malcolm challenged the conventions of humanity, race, intellect, religion, and, most importantly, the hypocrisy of American democracy.

Born in Omaha, NE on May 19 1925, Malcolm’s parents challenged racism in Nebraska and their home was burned to the ground; the family then relocated to Lansing, MI where his father was killed under suspicious circumstances. Malcolm’s mother was devastated by her husband's death and would eventually be institutionalized. Despite excellent grades, Malcolm dropped out of school at 15 and drifted into a life of crime. A 20 year-old Malcolm was imprisoned where he met a man named "Bimbi" who convinces him to develop his mind. In 1948, Malcolm’s siblings introduce him to the tenets of Elijah Muhammed and the Nation of Islam (NOI). Upon his release, Malcolm takes the name “Malcolm X” and becomes a minister in the NOI. In 5 years he would raise the NOI membership to 40,000.

Malcolm became an international force in the movement for Black liberation; his commitment transcended his role as a minister in the NOI. He challenged American hypocrisy on street corners, the pulpit, academia, and the press. His influence made enemies within the NOI and the highest echelons of American power. In 1965, Malcolm was assassinated while speaking in Harlem at the Audubon Ballroom.

Malcolm’s life and best work reveals that in 2022 America’s commitment to anti-blackness remains steady, but not controlling, especially if we remain committed to truth and action.

“The greatest mistake of the movement has been trying to organize a sleeping people around specific goals. You have to wake the people up first, then you'll get action.” – Malcolm X